How three Modesto-area schools are changing to better serve students with disabilities

Original article found here.

Three Stanislaus County schools are changing the way they offer special education in order to keep those students in classrooms with their nondisabled peers for more of the school day.

Aspire Public Schools is pairing special and general education teachers. The co-teaching model is backed by research showing all students stand to benefit socially and academically when students with disabilities are included in general education classrooms.

“We are hoping that keeping kids in their classroom — supporting them socially and emotionally alongside their peers — will actually foster a sense of belonging that they didn’t have during the pandemic,” said Meghann Cazale, director of special education for Aspire’s Central Valley Region.

Aspire is a nonprofit that runs free public charter schools in low-income areas in Los Angeles, the Bay Area and the Central Valley, according to its website.

In Stanislaus County, its schools are Aspire Summit Charter Academy for grades TK-5 in Ceres, Aspire University Charter School for grades TK-5 in Modesto and Aspire Vanguard College Preparatory Academy for grades 6-12 in Modesto. These schools serve more than 1,400 students combined, most of whom are Latino, according to their websites.

Students with disabilities account for 7% to 10% of elementary students and 15% to 20% of secondary students across the organization’s near 40 California schools, Cazale said. About 14% of public school students nationwide receive special education services, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Public schools often conduct special education services in segregated environments, separating children with disabilities from their typically developing peers. In fall 2019, 65% of students with disabilities spent at least 80% of their school day in general education classrooms, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Additionally, Black, Latino and Native students are disproportionately referred to special education, and then are more likely to be placed in segregated learning environments and be disciplined, according to research from the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

The co-teaching model aims to disrupt these trends by giving all students access to the same social and academic experiences while providing the support they need.

Aspire staff will receive training from the CHIME Institute, a nonprofit that runs a TK-8 charter school in Woodland Hills. CHIME Charter School has used co-teaching since it was founded in 2001, Executive Director Erin Studer said.

“Some of the best people to train other teachers are teachers themselves,” Studer said.

Every CHIME class has a general education teacher, and special education teachers rotate among three to four classes, Studer said. They work with aides and service providers like speech counselors to administer everything students may need within the classroom.

The organizations secured a two-year, $659,000 grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to support monthly meetings, visits and the creation of an internal platform for communication and coaching, Cazale said.

PANDEMIC AFFECTS CO-TEACHING PROGRESS

Aspire long has sought to integrate students with disabilities for as much of their school day as possible, Cazale said. School leaders encountered CHIME’s co-teaching structure when searching for ways to do more to bring students with disabilities up to grade level, she said.

Schools are adopting co-teaching in various stages. The pandemic’s emotional and physical toll on staff have complicated logistics, school leaders said.

Aspire Summit Charter Academy Principal Zachary Dickinson said staffing shortages have affected his timeline as teachers quarantine and substitutes step in.

“It definitely pivoted where we had hoped to be this year,” Dickinson said.

School leaders at the TK-5 school in Ceres are spending this year planning — creating schedules, setting aside time for teachers to prepare and sharing information.

University Charter was one of the first Aspire schools to begin co-teaching, Cazale said. But she said staff turnover and a location switch led school leaders to back up into the training phase.

Next door, Aspire Vanguard College Preparatory Academy launched co-teaching in some math and English classrooms this year, Principal Jacob Weiler said.

Though adjusting to a new system is challenging, especially during the pandemic, Weiler said positive data on co-teaching’s impact makes it a change worth pursuing. “It’s kind of a no-brainer for me,” he said.

Co-teaching by definition lowers staff-to-student ratios. That means more teachers available to cater instruction to students’ varying academic needs and more adults to build relationships with students — both areas brought into focus by the pandemic.

“It’s a critical part of students feeling seen and supported and understood,” Weiler said.

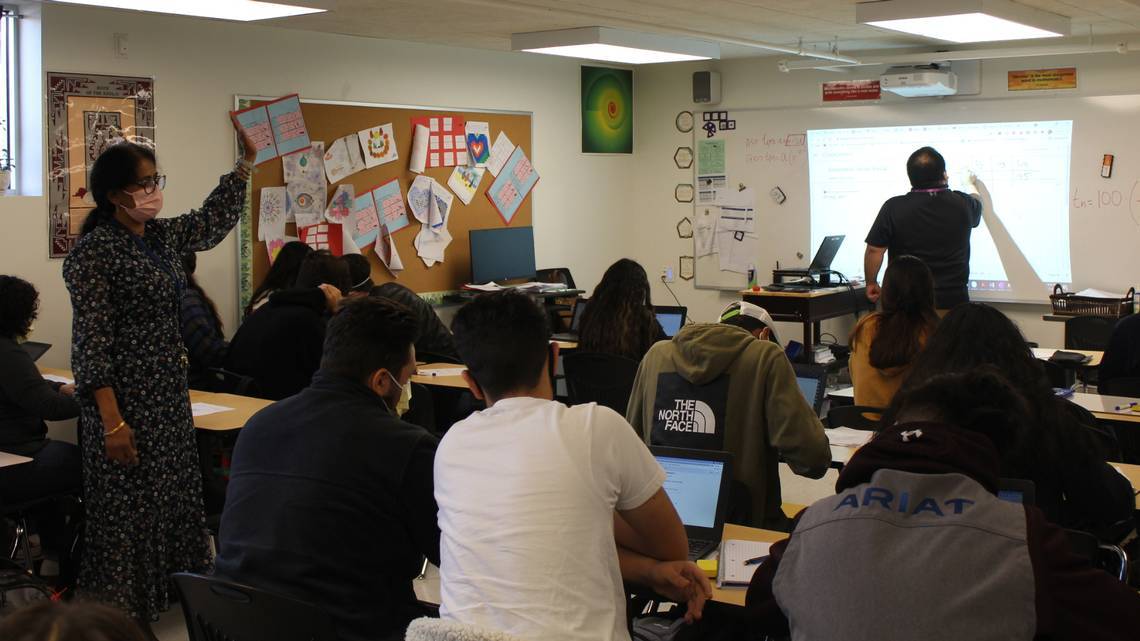

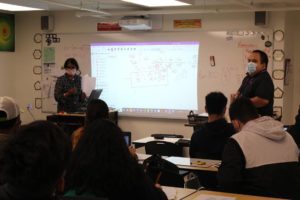

In a math class on Friday morning at Vanguard, a general education teacher and education specialist, or special education teacher, took turns instructing. They moved around the room to help different students at the same time.

An education specialist in a nearby English class worked with a few 10th-graders in the corner. The group likely included students with learning disabilities as well as nondisabled students who needed extra help, Weiler said. A general education teacher oversaw the rest of the group.

Weiler has attended special education meetings where parents state they don’t want their child excluded. They seem enthusiastic to know their child won’t be “othered,” he said.

“Trying to create classrooms where there’s a culture of belonging is really important,” he said.

Emily Isaacman is the equity reporter for The Bee’s community-funded Economic Mobility Lab, which features a team of reporters covering economic development, education and equity.

Your contribution helps support the Lab.

Click here to donate to the Lab through the Stanislaus Community Foundation.

Click here to learn more about the Lab.

Read more at: https://www.modbee.com/news/local/education/article255878981.html#storylink=cpy